Eczema Types

Stages of Eczema

Eczema-Ltd III is for all types and stages of eczema. Eczema is often called dermatitis (inflamed skin), affects people of all age groups, but is most common in infants and young adults.

The beginning of eczema symptoms can cause a redden rash and sometimes have blisters that will weep fluid. During this stage and later stages, the skin will alway be itchy, with the skin having an appearance of a brown color and scales. In almost every case, eczema itches. Eczema can be widespread or limited to a few areas. Atopic eczema, also called atopic dermatitis, is the most common form of eczema. Eczema runs its course through three distinct phases: acute, sub acute, and chronic.

The usual symptoms associated with the acute stage of eczema include pain, heat, tenderness, and possible itching. The affected areas are characterized by extreme redness and drainage at the lesion site. In acute eczema you would experience vesicles, blisters, and intense redness of the skin. The skin surface will sting, burn, or may itch intensely. The common examples for this stage of eczema would include acute contact eczema, acute nummular eczema, stasis eczema, and pompholyx eczema. The standard courses of treatment at this time would include cold wet compresses, antihistamines, antibiotics, and possibly a short-term course of steroids. The acute disease typically is characterized by inflammation, redness, swelling, and itching, as well as some blistering and oozing. Skin biopsies show inflammatory cells and swelling.

The sub acute phase of eczema includes symptoms associated with skin redness and crusting; however, there is no extreme swelling. You may observe redness, scaling of the skin, fissures, and a parched or scalded appearance to the skin. People in the sub acute phase tend to complain about the symptom of itching more than the pain. The itching in the sub acute phase is generally slight to moderate with possible stinging and burning. The common examples of the sub acute phase include contact allergy, irritation, atopic eczema, stasis eczema, nummular and asteatotic eczema. The basic course of treatment at this time would include a topical steroid, emollients, antihistamines, and antibiotics. The sub acute disease typically is characterized by inflammation, redness, swelling, and itching, as well as some blistering and oozing. Skin biopsies show inflammatory cells and swelling.

Individuals with lesions developed over three months are referred to as having chronic eczema. Itching is a predominant symptom in this phase as well and scratching causes the lesion to worsen. In the chronic stages of eczema the skin would show a thickened and or fissuring appearance. At this time you would experience a moderate to intense itch. Chronic eczema most occurs in atopic eczema and lichen simplex chronic eczema, fingertip eczema, and hyperkeratosis eczema. Again your standard courses of treatment would include an antihistamine, antibiotics, emollients, and possibly a topical steroid. Chronic dermatitis is identified by thickened, leathery skin with excess ridges, as well as dark and dull skin. Under the microscope, the outermost (epidermal) skin layer is seen to proliferate and become elongated.

Individuals with eczema often find that their symptoms tend to worsen in the winter months due to decreased humidity in the home or office.

Types of Eczema

Eczema is a general term for any type of dermatitis or "inflammation of the skin." All types of eczema cause itching and redness, and some will blister, weep, or peel. Although the term eczema is often used when referring to atopic eczema, there are several other skin diseases that are forms of eczema as well, including:

- Atopic Eczema is an allergic reaction of the skin to items exposed to by touch or sprayed upon or anxiety or fear.

- Contact Eczema is eczema caused by physical contact with an irritant or allergen such as greases, tars, or rough surfaces.

- Discoid Eczema appears in as a round coin-shaped areas on the skin (also known as nummular eczema).

- Dyshidrotic Eczema appears as itchy blisters on the hands, fingers and feet and the soul of the foot.

- Eczema Herpeticum is a very rare contagious eczema infection caused by herpes simplex virus. Please see your infectious disease doctor.

- Eczema Craquele has symptoms of a dry, parched skin surface with fine cracks or a 'cracked paving' appearance while being scaly and itchy.

- Infantile Eczema (also known as cradle cap) is an itchy,scaly eczema condition on the top of babies heads.

- Juvenile Plantar Eczema is foot eczema of children and adults feet usually caused by shoes and socks.

- Light Sensitive Eczema is eczema caused by over exposure or sun sensitivity to the face, arms, and legs.

- Seborrheic Eczema is very sensitive inflammatory eczema areas that are formed by oily yellow scales found on the face, scalp, skin folds, etc. Dandruff is a mild form.

- Varicose or Stasis or Venous Eczema are the same type of eczema and is caused by poor circulation in the legs.

Itching occurs with nearly all forms of eczema, varying from mild irritation to a hopelessly distracting and distressing symptom that makes life miserable for the sufferer and others involved.

Redness is usually present in eczema and this redness can fluctuate, appearing bright red at some times of the day while at others it is barely noticeable. The redness is usually most obvious when you are hot, have just exercised, or after a hot bath.

Eczema is usually dry, making your skin feel rough, scaly, and sometimes thickened. Dryness reduces the protective quality of the skin, making it less effective at protecting against heat, cold, fluid loss, and bacterial infection.

In severe eczema, or after a prolonged period of scratching, the skin's protective character can be reduced further and the skin becomes wet with colorless fluid that has oozed from the tissues, sometimes mixed with blood leaking from damaged capillaries (small blood vessels). Wetness usually occurs when eczema is at its most itchy and is very likely to become infected.

Some wetness may come from small vesicles (pin-head blisters), which burst when scratched. These are most commonly found on the hands and feet, along the edges of the digits or on the palms or soles.

Understanding Eczema Skin

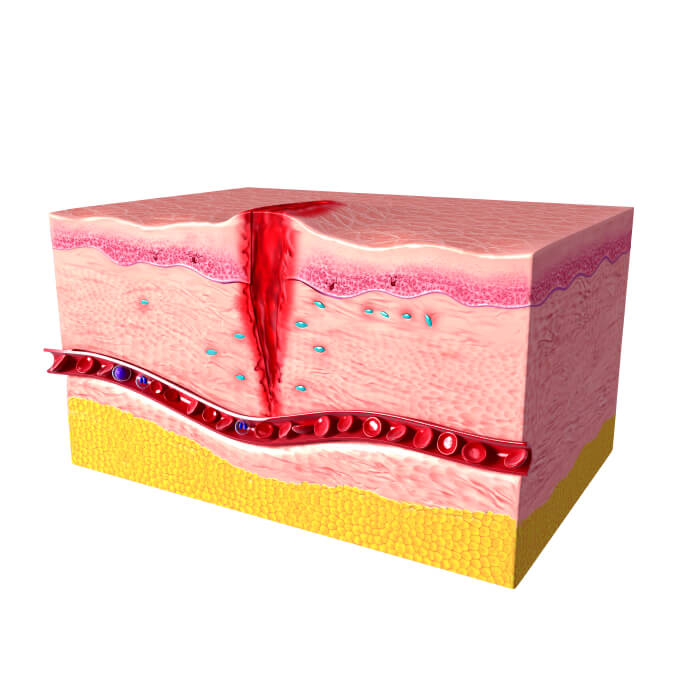

To understand eczema, we must begin with an understanding of the composition of the skin itself. The skin is comprised of three layers: epidermis, dermis and fat.

The outer layer of the skin is the epidermis, which contains sheets of epithelial cells called keratinocytes. These keratinocytes are produced at the junction between the epidermis and the second layer of skin, the dermis. The epidermis is supported from below by the dermis.

The epidermis contains many layers of closely packed cells. The cells nearest the skin's surface are flat and filled with a tough substance called keratin. The epidermis contains no blood vessels - these are all in the dermis and deeper layers. The epidermis is thick in some parts (one millimeter on the palms and soles) and thin in others (just 0.1 millimeter over the eyelids).

Dead cells are shed from the surface of the epidermis as very fine scales, and are replaced by other cells, which pass from the deepest (basal) layers to the surface layers over a period of about four weeks. The dead cells on the surface take the form of flattened, overlapping plates, closely packed together. This layer is known as the stratum corneum and is remarkably flexible, more or less waterproof and has a dry surface so that it is inhospitable to microorganisms.

The second layer of the skin or dermis is made up of connective tissue, which contains a mixture of cells that give strength and elasticity to the skin. This layer also contains blood vessels, hair follicles and roots, nerve endings, and sweat and lymph vessels and glands. The elements of the dermis all carry messages or fluids to and from the epidermis so it can grow, respond to the outside world and react to what goes on inside the body.

Underneath the dermis is a layer of fat, which acts as an important source of energy and water for the dermis. It also provides protection against physical injury and the cold.

In eczema, the main problems occur in the epidermis where the keratinocytes become less tightly held together. As a result, they become vulnerable to external factors such as soap, water and more aggressive solvents such as those used as part of work or hobbies. These solvents dissolve some of the grease and protein that contribute to the natural barrier of the skin. Once this process has begun, the skin may become inflamed as a reaction to minor irritation such as rubbing or scratching. This, in turn, makes the eczema worse and a cycle of irritation, inflammation, and deterioration of eczema becomes established.

As part of this cycle, the skin becomes less effective as a barrier. It is less effective at preventing damage from solvents and abrasive materials acting from the outside, and it is also more likely to lose body moisture from within. In a small patch of eczema, this can mean just a few vesicles (very small bubbles in the skin) bursting and leaking water. As the eczema gets worse, the fluid may come from the dermis and include blood from broken capillaries. When severe eczema covers a large percentage of the body surface, it is possible to lose substantial amounts of body fluid, blood and protein through the skin. In addition to these materials, the body can lose heat from the skin, which can become important in people who are physically infirm.

The barrier function of the skin is reduced further when scratching occurs and breaks are gouged in the skin by finger nails. As with solvents, this fuels the eczema and is termed the 'itch-scratch cycle.' When skin becomes broken and there is a mix of blood, fluid, and protein on the surface, there is a high chance of infection. This infection is usually bacterial and will add to the symptoms and severity of the eczema.

The epidermis is where the environment collides with the body's immune system. Usually the immune system reacts only to parts of the outside world that present a danger, such as insect bites. In many people with eczema, however, the immune system reacts more vigorously than usual to a wider range of normally harmless influences such as animal dander (small particles of hair or feathers), pollen and house-dust mite. As these trigger allergic reactions, these substances are known as allergens. The immune system tries to destroy allergens by releasing a mixture of its own irritant substances, such as histamine, into the skin. The result is that the allergen may be altered or removed, but at the expense of causing soreness and making the skin fragile so other problems can develop, such as bacterial infection or damage from scratching.